|

When she was mortally

injured by a hit and run driver outside the University of California, Berkeley in November, 1944, the police report gave her

name as Mrs. Elizabeth Antoinette White. But on her death certificate, her husband insisted on adding: “Also known as

Princess Der Ling.” She died virtually forgotten - we may assume the clerk who had

to make her Chinese name and title fit the tiny space on the California death certificate grumbled over the task. But her

entertaining and insightful writings, as well as her desire to build bridges between east and west, still have much to teach

the present about China’s past and its future.

A memoirist, ranconteur,

and a European-educated, multi-lingual Asian woman who gleefully crossed all the lines of cultural expectations both oriental

and occidental, Princess Der Ling was a unique character on the stage of late Qing and early Republican China. A favorite lady-in-waiting to the Empress Dowager Cixi, she became that hated woman’s greatest apologist

and defender; and after moving to the United States in the late 1920’s, Der Ling sought through her seven books, numerous

articles and lectures to create understanding of China and Chinese history, while at the same time showing that a true daughter

of China could live western like the best of them.

Der Ling, as a personality

more than as inside chronicler of one of the most secretive courts in history, has been floating at the margins of Qing

dynasty history and historiography for some thirty years. She has appeared in

almost as many media as the empress dowager she tried to make the world understand: as a supporting character in Li Hanxiang’s

1976 film, The Last Tempest (speaking with a pronounced American accent), in Sterling Seagrave’s blockbuster

1992 biography of Cixi, Dragon Lady: The Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China (Knopf)-in which Seagrave makes an effort

to rehabilitate not just Cixi but Der Ling-and most recently in a University of Edinburgh thesis by Dr. Shiou-yun Fang, Images, Ideas, Reality

(2005). In addition, Der Ling’s account of being a student in Isadora Duncan’s early dance classes in Paris form

a strong part of the core of Peter Kurth’s acclaimed 2001 biography Isadora: A Sensational Life, and is in fact

where I first discovered Der Ling the person and the writer.

|

|

| Mr. and Mrs. Thaddeus C. White |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

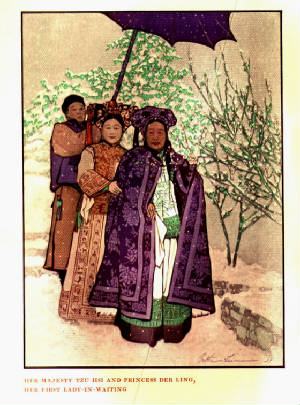

| Painting of Der Ling and Cixi by Bertha Lum, 1933 |

For Bertha Lum's portrait of Der Ling, click here

|

| Der Ling's personal seal |

With

most of her books long out of print and her once ubiquitous face vanished from the news columns, Princess Der Ling [1885-1944]

is known to few people today. Yet this writer and cross-cultural celebrity has

as much to say about today’s congruence and collisions of East and West—in terms social, political, historical

and cultural—as she did over 80 years ago.

Like

that of Puyi, China’s last emperor, whom she first knew as an infant at the court of his imperial relative, Empress

Dowager Cixi, and would later try to help when his creditors came calling, Der Ling’s life writ large touches on issues

broader than even the vast Chinese landscape where she was born. Through the

courage of this Western-educated Manchu woman, who shocked Peking society dancing the Charleston, who fascinated gullible

New Yorkers by appearing at the opera in imperial Manchu court garments, a vista opens on an international cultural history

of the early- to mid-20th century.

Der Ling’s first and most famous book, Two Years in the Forbidden City (1912), which appeared the year the Manchu dynasty fell, glitters with the glamour

of a lost world, and served as an apologia not just for the ex-dynasty but for its most reviled ruler, the Empress Dowager

Cixi (1835-1908), the woman Der Ling had served as court lady, translator and surrogate daughter from 1903-1905. With the disintegration of the Romanov empire five years later, and the dispersal of its uprooted aristocrats

and intelligentsia through the world, a culture of the displaced celebrity launched this self-promoting Asian woman with the

tissue-thin title (and an American grandfather she never acknowledged) on a flood of general fascination with throneless royalty

and exotic pretenders.

My book is the first to deal with Der Ling as a phenomenon

of the fragmented, delirious era in which she lived, putting her recollections to the test while maintaining my opinion that

her memories of the last great Asian court and its society have much to teach us about the period, the people and East-West

relations. PartI deals with Der Ling’s beginnings, from her birth in Peking in June 1885 to her upbringing by her diplomat

father in Tokyo and Paris and her Western education; Part II covers Der Ling’s summons from Paris to the imperial Chinese

court by the Empress Dowager Cixi and her experiences of learning to know, fear and love this much-misunderstood woman; and

Part III deals with Der Ling’s authorship of her seven books and a critical appraisal thereof; her marriage to an American

and move to America, where her mystique flowered in an atmosphere of fascination with all things oriental and then died out

almost as totally as it had flourished.

|

|

|

|